It was a sweltering summer morning in 1964 when an off-duty New York City police officer shot and killed a 15-year-old Black boy named James Powell, sparking several days of rioting in Harlem.

Powell had been sitting on the front steps of an apartment building with friends across the street from the school he was attending on the Upper East Side of Manhattan when the superintendent of the building, a White man named Patrick Lynch, sprayed them with water, telling them he was going to “wash the black” off them.

The teens responded by throwing garbage can lids and bottles at him, chasing him into the apartment building where he locked the door behind him, according to New York Times articles archived from that period.

New York City Police Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan said he was inside a store next to the doorway of the building on his day off when he heard the sound of glass shatter. He stepped outside to investigate and spotted Powell and his friends banging on the door of the building with garbage can lids.

Gilligan claimed he pulled out his badge and identified himself as a cop and told them to stop banging on the door but Powell pulled out a pocket knife and came charging towards him making him fear for his life which is when he opened fire, killing the teen.

But the dozens of teens who witnessed the shooting told investigators they never saw a knife. They also said the cop who was not in uniform never said a word before opening fire. One girl said Powell was even smiling before he was shot and killed.

It turned into six nights of rioting in Harlem; the first of many more riots to explode in poor Black communities throughout the country over the next five years following confrontations between White police officers and Black citizens.

The riots shocked the nation at a time when most Americans were just getting used to the idea of Martin Luther King Jr.’s peaceful protests in the South to end segregation.

The riots would also change the course of American history, according to the books, The Harlem Uprising by Christopher Hayes and From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime by Elizabeth Hinton, which provided much of the information for this article along with several independent studies, government reports and the very extensive New York Times archive system.

The War on Crime

The unprecedented violence in poor Black neighborhoods turned President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty into the War on Crime, a permanent war on the people that has been escalated and rebranded with every presidential administration over the past six decades at the cost of social programs addressing poverty – which would have done a better job in reducing crime, according to multiple studies.

Today the United States has the highest incarceration rate in the developed world as well as the highest rate of police killings with an average of three people a day killed by police, many who are mentally ill or addicted to drugs.

The United States also has one of the highest poverty rates in the developed world behind countries like France, Germany, Canada and Japan where only a handful of people are killed by cops each year and where crime rates are much lower than in the United States. And multiple studies show that hiring more cops has little or no effect on crime.

Even after violent crime rates sharply declined in the early 1990s, billions of dollars were poured into the American criminal justice system to hire hundreds of thousands of new cops resulting in a sharp increase in misdemeanor arrests in poor Black neighborhoods where the Constitution has long been ignored.

These include low-level arrests like disorderly conduct, obstruction, drug possession, loitering and panhandling. Victimless crimes that fill the courts and drain defendants of their money, placing them further at risk for arrest if they are unable to pay the fines.

Despite the obvious failures of the American criminal justice system, decades of fear-mongering conditioning from the government has most citizens balking at the thought of defunding the police, viewing it as a form of blasphemy while remaining divisive over social programs that would do a better job of reducing crime.

And even when politicians pretend to care about police abuse, their only solution is to keep feeding the criminal justice machine with Republicans calling for more “law and order” and Democrats calling for more “community policing,” both which are code for maintaining social order in poor Black communities. A political good cop/bad cop routine that costs taxpayers billions of dollars a year while destroying thousands of lives, doing nothing to resolve the real issue of poverty.

Civil Rights Act

The July 16, 1964 shooting of James Powell took place two weeks after President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law which had been opposed by about one-third of Americans.

It also took place the morning of the Republican National Convention in San Francisco when Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater – who opposed both the Civil Rights Act and the War on Poverty – accepted the party’s nomination for the presidency, vowing to restore law and order if elected.

Johnson had been in office only eight months following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and was running on his Great Society platform where his goal was to eradicate poverty and racial injustice. He had declared his War on Poverty two months after taking office during his State of the Union address in January 1964. He then succeeded in passing the Civil Rights Act which had been proposed by Kennedy before he was assassinated.

But a New York Times poll following the uprising in Harlem revealed that many residents of New York City were having second thoughts about granting Black people civil rights. And Republicans began painting Johnson as being soft on crime as cities like Rochester and Philadelphia experienced their own riots within a month of the Harlem riot.

Johnson won the election and declared his War on Crime the following year in 1965 with the introduction of the Law Enforcement Assistance Act which for the first time in history funneled federal funds to local and state law enforcement agencies for training, equipment and the hiring of more cops.

Johnson also ordered the FBI and the U.S. Army to offer training to local and state law enforcement agencies throughout the country, marking the beginning of the militarization of police.

In 1967, following deadly riots in Detroit and Newark, President Johnson created a committee to investigate the reasons that led to the riots in order to prevent future riots.

The Kerner Commission determined the riots were rooted in the systemic racism that kept Black people in poverty-stricken neighborhoods without access to adequate housing, secure jobs and quality education at a time of great prosperity for most of the nation – which is exactly what Black people had been saying for decades to deaf ears.

The Escalation

Johnson’s War on Crime would gradually overshadow the War on Poverty for the remainder of his term as federal funding for police and weapons increased while it decreased for programs that offered job training and remedial education to young people in those communities.

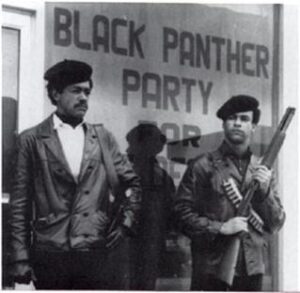

But the more aggressive the police became, the more aggressive the people became and militant groups like the Black Panthers emerged who began monitoring police in their neighborhoods while carrying rifles which was legal at the time in California. But that led to police becoming even more aggressive, killing many members of the Black Panthers.

But the more aggressive the police became, the more aggressive the people became and militant groups like the Black Panthers emerged who began monitoring police in their neighborhoods while carrying rifles which was legal at the time in California. But that led to police becoming even more aggressive, killing many members of the Black Panthers.

Over the next several decades, the War on Crime would be escalated and turned into the War on Drugs under Republicans Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan who both spent billions in federal dollars building new prisons and hiring more cops at all levels of the government.

Democrat Bill Clinton launched an unofficial war on “superpredators” with the signing of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 which spent billions on more cops and prisons, including the addition of 6,500 cops to police our schools.

Republican President George W. Bush then launched the War on Terror following the 9/11 attacks that gave law enforcement much broader powers under the Patriot Act to investigate and incarcerate American citizens without probable cause. Bush also launched the Department of Homeland Security that seems to do a better job monitoring activists than investigating terrorists.

And presidents Barack Obama, Donald Trump and Joe Biden all expanded the school resource program where there are now more than 25,000 school resource officers policing our schools across the nation –which has done nothing to stop school shooters considering they tend to run and hide along with everybody else when the shooting starts.

But school cops have played a strong role in criminalizing students over issues that used to be disciplined by detentions or suspensions doing their part to feed the school to prison pipeline that keeps the criminal justice industry growing.

Meanwhile, income inequality in the United States has increased with every president since President Johnson which is another factor that can lead to an increase in crime but that is rarely discussed by politicians.

Harlem

The initial target of Johnson’s War on Crime were the inner cities, poor Black neighborhoods that had emerged during the Great Migration, a period starting in 1910 when Black Americans from the South migrated to cities in the Northeast, Midwest and West to seek employment and to escape the lynchings and segregation.

But most encountered a different kind of racism that still kept them segregated; a much more subtle style of racism that was not written into law but practiced daily among those in positions of power, including police, politicians and employers.

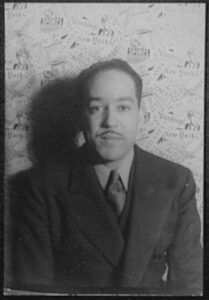

Harlem, a neighborhood in Manhattan’s Upper West Side, became the cultural center of Black America during the Harlem Renaissance, a very creative and innovative period lasting from 1918 to the 1930s when Black musicians like Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Cab Calloway would perform for White audiences, and writers like Langston Hughes would recite poetry to jazz music, a precursor to today’s hip hop music.

But the neighborhood fell on hard times during the Great Depression and remained destitute during the years after World War II, a period of great prosperity for White America, mostly due to the GI Bill which allowed returning veterans to obtain low-interest loans for suburban homes.

The loans were not available to Black veterans through a process known as redlining in which banks refused to lend money to people in Black neighborhoods, a discriminatory practice which still affects many Black Americans today since their ancestors were unable to build generational wealth.

The postwar years were also a period when labor unions thrived in the nation’s major cities which contributed to the prosperity by allowing working class men to earn enough money to support a family and live in the suburbs.

But the unions were allowed to discriminate against Black people, denying them the opportunity to obtain well-paying labor jobs, so many Black men were either unemployed or stuck in low-paying jobs with no room for advancement.

Then there were the aging deteriorating rat-infested homes without adequate heat that were not maintained by White landlords as well as the inferior public school education resulting from a lack of funding that kept Black children from advancing.

By the time Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law, many Black Americans in Harlem were skeptical because New York City had an anti-discrimination law in place since the late 1940s that did nothing to keep them from being discriminated against.

And they had already spent decades protesting these issues through peaceful protests, sit-ins and boycotts to no avail.

The Shooting

James Powell, who one year earlier attended the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech, was attending summer school for a remedial reading class in the summer of 1964 when he was killed.

He was the only son of a widow, one of dozens of Black students who had been bussed in from the Bronx to attend summer school at Robert F. Wagner Junior High in the predominantly White neighborhood of Yorkville in Manhattan. It was about 9:20 a.m. and a very humid 74 degrees Fahrenheit as dozens of students congregated on the sidewalks in front of the school, waiting for their 10 a.m. class to begin.

Powell and his friends were sitting on the front steps of an apartment building when they were sprayed with water by the superintendent of the building who had been watering plants. Patrick Lynch told police he inadvertently sprayed them but the students said it was deliberate because he referred to them in racial slurs while expressing annoyance they were sitting on the steps.

Powell would be shot dead within minutes.

“Why did you shoot him?” a teenage friend of Powell asked the cop, according to the teen’s statements to investigators.

“Because of this,” responded the cop while pulling a badge from his pocket and clipping it to his shirt.

A knife was found several feet away from Powell’s body in between two parked cars but it was never determined without a doubt that it was used by Powell to threaten the cop. It was also a period of great corruption within the NYPD even worse than today and they would frequently plant weapons on people they killed.

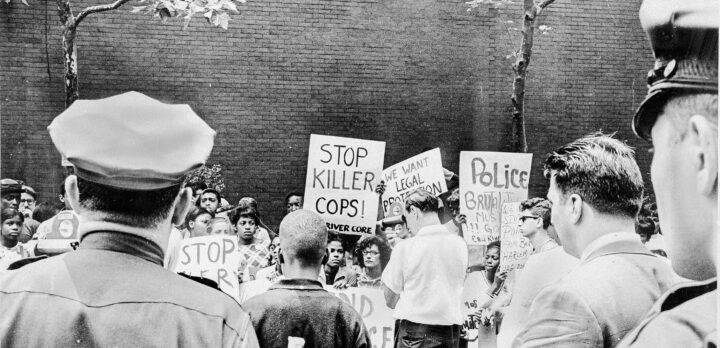

After two days of peaceful protests, more than 150 Black protesters who had attended Powell’s funeral in Harlem marched to the NYPD’s 28th Precinct to demand the arrest of Gilligan.

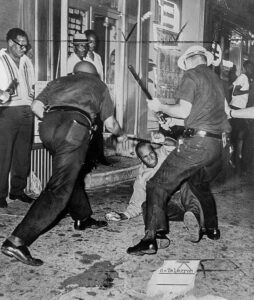

The cops ordered them to disperse but several protesters planted themselves on the sidewalk in front of the station, refusing to move. The NYPD bussed in more than 200 cops who charged at the demonstrators with batons, beating anybody who would not disperse.

The protesters broke up into smaller groups and began smashing windows, looting stores and torching cop cars with Molotov cocktails, spending the next six days pelting cops with bottles from rooftops who responded by firing their revolvers back towards the rooftops. The riot spread to the Bedford–Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn which had turned predominantly Black in the mid 1930s and were experiencing the same issues.

Gilligan was cleared by a grand jury and spent the next few years on paid sick leave for an old back injury before he was forced to retire in 1968. He spent the rest of his life quietly collecting his pension before he died in 2014 at the age of 84. Powell would have been 74 if he were alive today.

In 1966, New York City Mayor John Lindsay tried to add four citizens to the Civilian Complaint Review Board that was made up of three police officers in charge of reviewing citizen complaints against police.

But the police union, the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, became political for the first time in its existence, spending more than a million dollars in scare tactics advertising to force the issue on a referendum ballot where it was soundly defeated. It would be another two decades before citizens not carrying badges would be allowed on the Civilian Complaint Review Board.

In 1992, New York City Mayor David Dinkins, the city’s first Black mayor, proposed a bill to remove all cops from the review board, sparking the Patrolman’s Benevolent Association Riot where 4,000 off-duty cops, many of them drunk, flooded the streets around city hall in protest; blocking traffic, destroying property, attacking journalists and yelling racial slurs at the mayor while on-duty uniformed cops watched and did nothing.

Despite the union’s strong-arm tactics, the mayor fulfilled his goal the following year to remove cops from the Citizen Complaint Review Board but it really hasn’t done much to quell the abuse against citizens.

George Floyd

Compared to 1964, law enforcement and the rest of the country is much more diverse these days so the police abuse is much more multicultural, both perpetrators and victims, and we’re suppose to view that as progress. It has become blue versus any citizen who dares question their authority even though Black people still get the brunt of it.

The one difference are citizens with cameras as we saw in the summer of 2020 when a video surfaced showing a Minneapolis cop pressing his knee against the neck of a Black man named George Floyd for nearly ten minutes as the 46-year-old man slowly died, begging for his mother, shocking the country at a time when most Americans were stuck at home during pandemic lockdowns.

Floyd who was born into poverty and remained poor throughout his life was accused of trying to buy cigarettes with a counterfeit $20 bill after he had lost his job as as security guard during the pandemic.

It appeared, for a few weeks at least, the country had finally woken up to the reality of police abuse and were hellbent on making sure it did not happen again. A handful of Democrats were even calling to defund the police and cities across the country began discussing ways to scale back funding for police.

But then came the riots, the burning of buildings, the battles on the streets with police, the unleashing of decades of pent-up anger against the cops exploding in cities across the country. And soon the calls for defunding the police were twisted by the Police PR Spin Machine into calls for anarchy, lawlessness and mob rule.

Today almost three years after the death of Floyd, not only has funding for police increased, so have the senseless killings by police. And shocking videos remain a routine part of the news cycle with the latest from Tennessee showing the beating death of Tyre Nichols, a Black man killed by Black cops, who like Floyd died crying out for his mother.

But politicians are no longer calling to defund the police, knowing it would be political suicide, even though they never bothered to explain what it really means in the first place.

For starters, defunding the police in the most realistic sense does not mean abolishing the police. It simply means redirecting a percentage of tax dollars from law enforcement to address poverty which is the main driving force behind crime.

It’s about funding healthcare, housing and education while demilitarizing police and removing them from our schools and not expecting them to solve every little crisis and settle every dispute and serve as our imaginary superheroes when they are just as dysfunctional as the rest of us but with a license to kill.

It’s about investing in communities and people instead of cops and prisons.

But last year President Joe Biden vowed to fund the police with billions in pandemic money, continuing the cycle of political pandering and planting the seeds for the next wave of abusive cops and riots sure to follow which will be much more multicultural than in the past if you want to call that progress.

Please help the blog grow with more insightful and educational articles by making a donation and subscribing below.

Came here from your Twitter post. I read carlosmiller.com even before pinac. Glad to see you’re keeping on!